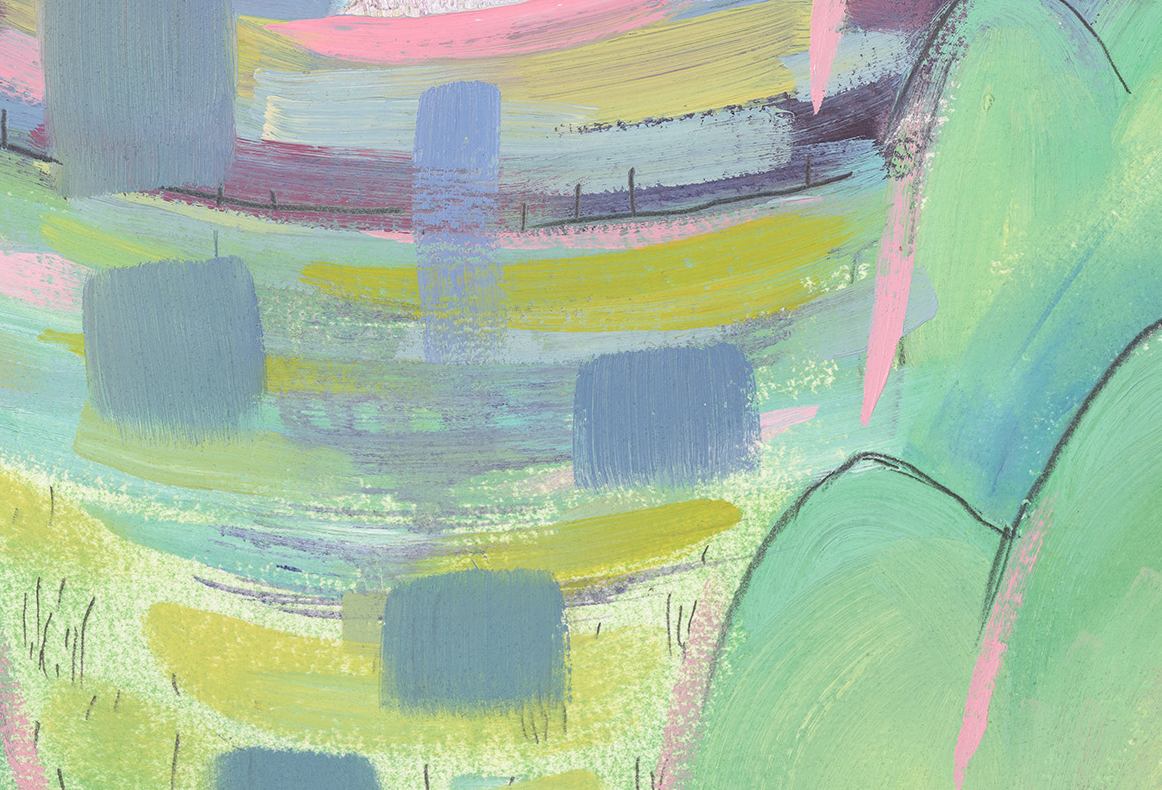

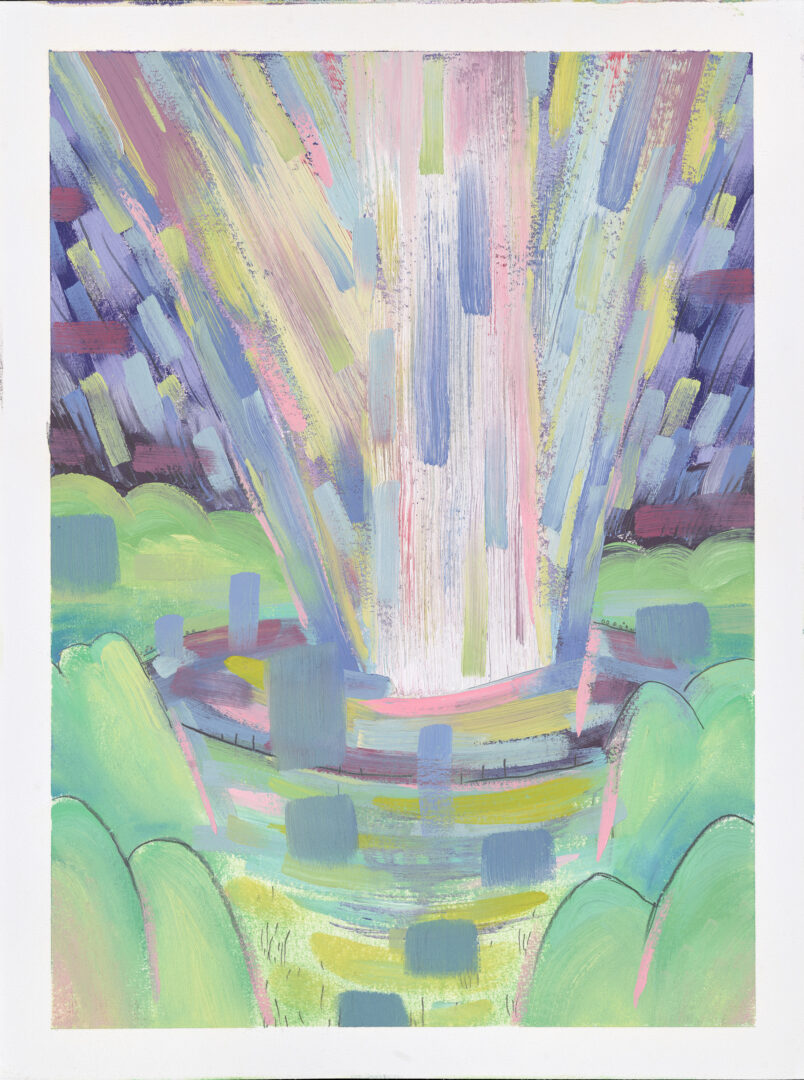

There is the experience one has when standing before a geyser: first, patient anticipation, an awareness of the minutia of one’s environment: birdsong, the quality of air, the dry form of rocks, the wind moving through tufted grass patches, how the light or the night falls on everything—then, the eruption. It is water, mineral-rich and boiling under the surface of the earth’s skin, heated by the Earth’s molten, iron heart. It is overwhelmingly powerful, but also safe to a point for us, because we have put cordons around it, and because it is predictable, yet also banal; we have copied it endlessly, in fountains, in water-parks, with the hose in the yard, and in our plumbing. A feeling of control over the world—and comprehension of it—brings us pleasure and gives us ease. At our cores, though, we also have a liquid heart, heated and pulsing with our iron-rich blood, coursing with all the incomprehensible, untalked-about things which churn in us until, it, too, erupts—powerfully, beautifully, and yet often painfully, as we touch the numinous vastness of self uncontrolled, banality negated: human, being like a brilliant upwelling and like a gravitational downwelling at once.

Graphically, this painting is compositionally inspired by 19th Century prints of fireworks (both European etchings and engravings and Japanese woodblock prints); they are the artful rendering of controlled explosions, calculated chemical combustions which create color to bring us awe and joy—depictions of light as it rises and falls, as it both fountains and rockets up, the spectacular ignition followed by a delicate flickering out while succumbing to gravity.