Dixie Icons: Re-Visioning the Dixie Myth opened September 7th, and there was a reception Saturday, September 10th at 7 PM at the Fire House Gallery. The works in the show are all prints, and were created in response to imagery used in the text Dreaming of Dixie: How the South was Created in American Popular Culture. Images of works in the show, along with accompanying statements can be found here. The theme dovetails with my content matter, and I’m really keen on addressing the visuality of these themes more directly. The Fire House Gallery is also a gallery which is quite supportive of printmaking, and it’s a pleasure to participate, support and be supported in my field.

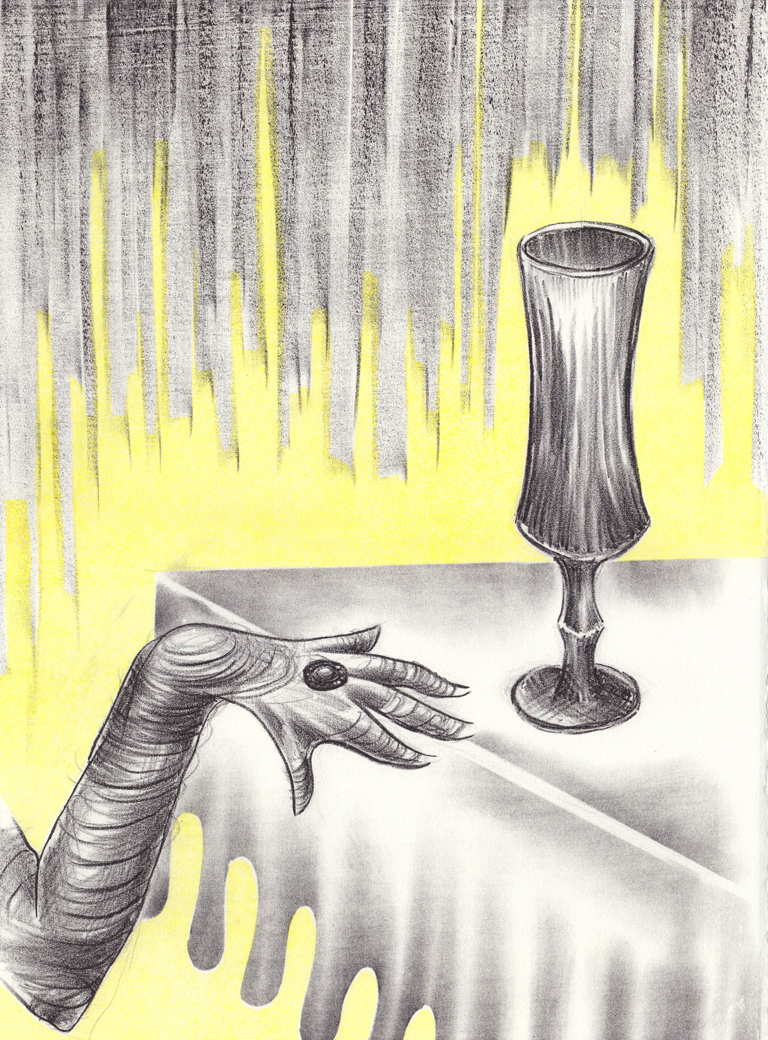

The image to the left is of the work made for Dixie Icons; it is a stone lithograph with monotype which was

drawn, processed and printed during a summer workshop run by Frogman’s Press in South Dakota, at the University of South Dakota in Vermillion.

This is the statement which accompanies my work for the Dixie Icons exhibit at the Fire House Gallery in Louisville, GA.

The work I’ve created for Dixie Icons was based on a Maxwell House Coffee advertisement from 1930. In it, a bunch of high society white folks are engaged in a lively dinner party, and in the background, a black servant stands holding a tray of what the ad-makers hoped we would presume was an aromatic and lovely coffee in a silver pot. This black man is portrayed in a stereotypical fashion, resembling Uncle Remus and Uncle Tom, while also simultaneously embodying the Noble Servant and various minstrel characters. It is easy for us, as a contemporary audience, to see how this man has been presented as an archetype of The Other, rather than as an individual.

The white people in the advertisement are just as exaggeratedly stereotypical, but the stereotypes they represent are aspirational for white people: glamorous, wealthy, beautiful, elegant, witty, fashionable, etc.–certainly anyone who has attended a dinner party knows that a table full of such types is rather unlikely. One could also say that the caricature of the black servant was also aspirational for white people—not, however someone they would aspire to be themselves, but someone they would aspire to—quite frankly—possess. Since times have changed, white perceptions of the Uncle Tom or Uncle Remus figure have also changed. Curiously, and unfortunately, white perceptions of white aspirational stereotypes have changed little.

The advertisement is a clear illustration of white privilege—the inequality of wealth and power which allows one to live a life of leisure, surrounded by expensive, fine things, while wearing beautifully tailored clothes. Such a lifestyle always comes at the expense of others, both literally and metaphorically.

In my body of work, I attempt to expose and undermine white privilege. Sometimes I try to be stealthy about it, as a direct confrontation is often received hostilely by those most invested in privilege, other times stealth is unnecessary, as whites tend not to want to examine our own privilege, or we deny it altogether.

In this work, To the Last Drop, I’ve chosen to single out a few visual elements from the advertisement: the glamorous woman’s hand, the form of one of the elegant stemware items, and the table. When I look at the gathering of revelers, I see people who have benefitted from a system of institutional exploitation. To me, the scene is creepy. It’s creepy because I see this dinner party as a ritualistic celebration of privilege. They’ve fed themselves, and now trade banter while awaiting the final ritualistic act of the meal: the imbibing of a dark Caribbean elixir—coffee. Coffee, the cultivation of which used up untold thousands of black lives; coffee, whose companion product is sugar, the cultivation of which is also responsible for thousands upon thousands of deaths.

Where I live in the United States–Miami, Florida—I often feel more kinship with the Caribbean than I do the US. The legacy of slavery, specifically as it relates to the coffee and sugar trade is strongly felt in the islands near my home, and the immigration patterns to our region make this legacy even more pertinent. Even in 2011, colonialism remains a highly charged, relevant discussion; here we feel very little distance from that era of the slave trade. Nearby Haiti remains economically devastated because of the complex political legacy of having been colonized and carved up for coffee and sugar production, even though it led the first successful slave revolt in our hemisphere.

I see these people—aspirational advertising sterotypes—at their dining table a year after the economic collapse of 1929, living it up, and I think about blood. I think about all the blood shed because of slavery, lost in beatings, in massacres, in revolution. I think about the danger of complacently accepting this presentation of whiteness, of the violence at the root of privilege, and of the inhumane acts which support glamour and luxury. I hope that To the Last Drop evokes a sense of dangerous consumption. I did not literally present either blood or coffee–the conversation surrounding privilege and violence is larger than that. I was aiming for a sense of greedy indulgence, almost vampiric in desire because I am often amazed at how we humans seem willing to gleefully consume each other in the pursuit and maintenance of privilege.