At the end of the long flat road heading westwards, most of which you spent stretched equally flat across the back seat of a station wagon during the dark of the pre-dawn, you find yourself finally seated upright on a high bench made of aluminum. The bench, and the boat to which it is attached, are hollow, and make resounding dull clangs and thunks when you move around. It is winter, and it is cold, and you are bundled into a mismatched assortment of clothes because you no longer own winter coats or hats or socks. You are wearing sunglasses shaped like a bubble over both eyes, because at the speeds you will be going, regular sunglasses would collect bug corpses in smears and smears and smears. You are with your uncle’s friends, a couple and their son, on their airboat.

They live next to the national park, in a small town that exists to be a pit-stop for those who travel the long flat road. You have spent a lot of time with them, these friends of your uncle, because, since your parents’ divorce, he has made it his job to be a parent to you. He is the one who feeds you, and gives you your allowance, and teaches you how to shoot guns and use knives and camp and cook and play poker and how to avoid being swindled or conned. He’s the kind of man whose life is usually lived like a cherry bomb in a mailbox, but, when taking care of you, he cleans the world up and forces it to make sense.

His friends have a big truck and a really fast speedboat and two ATVs and a Zodiac and this airboat, all of which are done up in an identical paint job, which you think is a little reckless because the dad’s job is to retrieve bales of drugs which have been dropped in the park, far, far, far from anywhere, and you think he must be pretty cocky, even though he seems super nice, because you figure that the matching paint job would make it easier to get caught.

You spend the afternoon bundled on the bench, clinging for your life, because you are absolutely flying over the grassy waters of the glades. There is a caged airplane propeller behind you, and the boat has no keel. It has a double rudders behind the propeller to change the path of the airflow, so that you turn, but the turns you make are drifts which glide—but glide isn’t fast enough of a word to be correct, you think screech or skid or careen would be better, only there isn’t any pavement around for miles. The roar of the engine is tremendous, and you can’t hear anything else. At one point, you cling to your younger brother, who is seated beside you. You are both exhilarated, and terrified. There are no brakes. You love it.

You spend the day being taught the pathways through the glades. The dad is a ‘cracker’ and grew up poor. He navigated these waters and grassways from his childhood, using a ratty canoe, or a flat raft, or once, when he was caught out by a storm, a single plank of wood. They have names you already barely remember, these “creeks” and “sloughs”, and there are islands which have their own names and you are learning nothing because you don’t have the skills to tell any of it apart. If you were alone, you would be terribly, terribly, terribly lost.

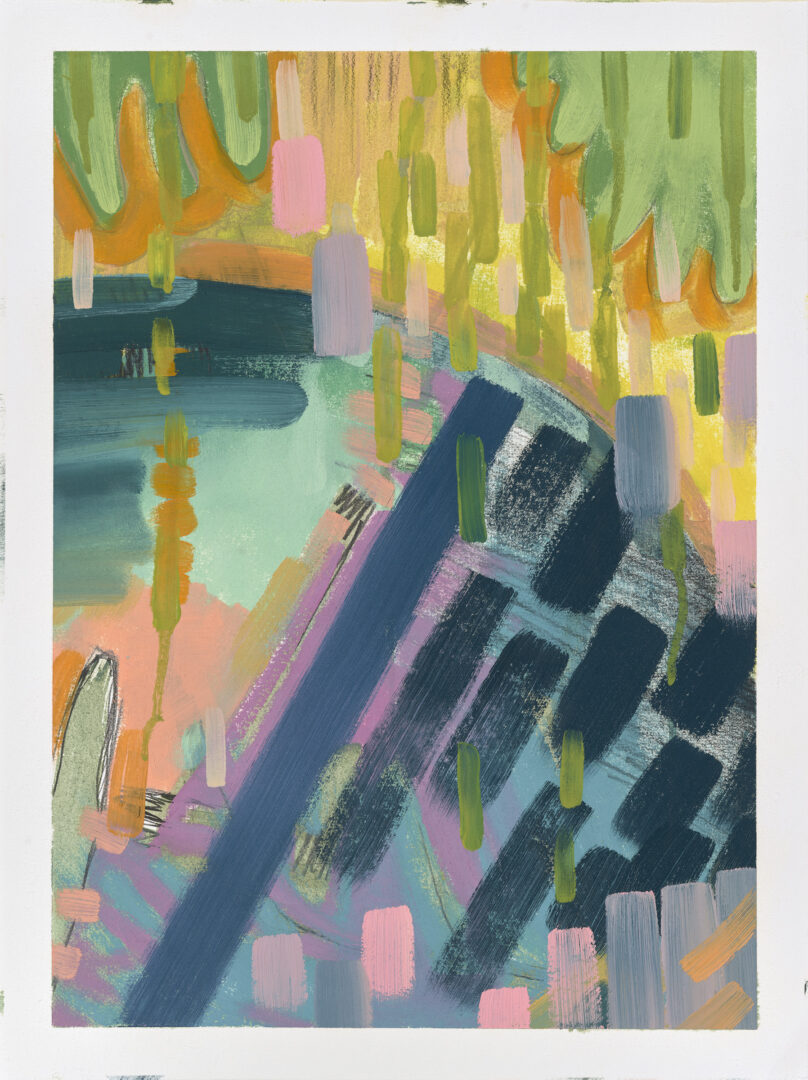

Sunset comes, piercing your eyes. This is unusual, because you don’t live where you can see the sun set over a long, earth-curved horizon. Your life is lived where the dawning sun incandesces in slow hints until it rises like a sudden blister over the water, so now you risk the eye damage and stare until you can’t, and then floating motes cover the world with orange and pink and yellow and purple, and then now a hint of evening comes blue but cold—a winter blue.

When it is finally dark, it is absolute, even though you look hard. You see nothing until you raise your gaze to the stars, endless and amazing. You think again about being lost and alone here, and know that you would die, though the dad that you are with did not, even though he was alone and your age in this place. It is because he wasn’t lost, you realize, so you decide not to ever get lost, and to never ever be lost if you are.

All around you there are silent snakes and warily lovelorn frogs and near-dormant alligators and nesting birds and flitting bugs and vibrantly-living everything out there, aware of you and your noisy group. The dad shows you how to tell the difference between the eyes of frogs and the eyes of gators when they reflect either red or white in the piercing strokes your headlamps make across the otherwise black space surrounding you. In the moment, you absolutely remember and can tell the difference, but later you forget which color is the frog, and which is the gator.

You spend some mildly guilty, exuberant hours after that gigging frogs—snatching them with long, three-pronged poles out of the waters you fly over, spears made just for this prey. You catch a lot, all of you, trading turns, one of you on each side of the boat, filling buckets with frogs—literally more frogs than you’ve ever seen in your entire life. The dad drives the boat in unpredictable twists and turns, aiming always for the glowing eyes, always for the right ones.

Soon, it seems that your buckets are already more full than you need. Your nose and cheeks sting from the cold, and you go back to the house. You might have tried the frog legs, which the family cuts from the body, slicing the frog in half, before dipping the severed legs in batter and plunging them into a turkey-sized outdoor deep-fryer—though you also might not have. It is one of those choices in your life which you will later not fully recall making.

You feel jangly and tired and vital and short-lived and loud, yet something inside you holds tight to everything that was still and majestic today. The long view, the moments when the engine was off and you could hear all the subtle vibrations of life around you as if you’d never heard sound before, the way the sunset speared you like a frog, your soul pronged by radiance, and the resounding darkness of the inhuman earth, cold and secretive, offering you endlessness.

As you fall asleep in the back bench seat of the long flat wagon, a slice of night tucked upside-down behind the glass over your head, the foam of your Walkman headphones over your ears, with bright, flitting, jeweled cassette tones of 80’s pop and new wave dancing in your unguarded teenage mind, you realize that you’ve fallen in love with something that you’ll never be able to touch because it will always be beyond your understanding, and you wonder how you’ll ever be able to live with this unfathomably deep feeling inside your heart. You close your eyes to warily sense this lovelorn longing going silent and near-dormant within you, this new, ponderously profound aching hope which will nest deeper inside than you know, and which yet already cuts you like a sawgrass blade, and maybe always will.